Home › Forums › Air and Sea › Naval › A review of Grand Fleets naval wargaming rules

- This topic has 3 replies, 3 voices, and was last updated 1 year, 10 months ago by

AdmiralHawke.

AdmiralHawke.

-

AuthorPosts

-

16/10/2022 at 22:19 #179156

AdmiralHawkeParticipant

AdmiralHawkeParticipantIntroduction

There’s a lot of choice of naval wargaming rules. So, having now found a set of rules that I like, and having played half a dozen different games using the rules, including Heligoland Bight 1914, the Scarborough Raid 1914, the River Plate 1939, Bantam Bay 1942, Savo Island 1942 and Kawakaze versus Blue 1942, I thought it time to write a review that others might find useful. I hope some of you will find it helpful. 🙂

Grand Fleets (http://www.mj12games.com/grandfleets/) was written by Daniel Kast and Kevin Smith, with the third edition of the rules published by Majestic Twelve Games in 2015. Majestic Twelve mostly publishes Sci-Fi rules: not an obvious pedigree for historic naval wargaming rules.

The basic rules cover surface actions from about 1890 to about 1945, encompassing movement, gunnery, torpedoes and damage resolution. The advanced rules add elements like critical hits, crew quality, fleet morale, evasive action, smoke screens, night fighting and radar, along with some simple rules for the effects of submarines and aircraft.

The rulebook contains six scenarios of varying obscurity: Ulsan, 1904; Cape Sarych, 1914; Dogger Bank, 1915; Cape Palos, 1938; River Plate, 1939, and Komandorski Islands, 1943. The rulebook includes 160 ship data cards representing over 50 different warship classes, almost entirely drawn from those six actions. The rules are intended for surface actions involving large warships and not designed for carrier battles, submarine attacks or coastal forces actions.

The game doesn’t need any special equipment: all you need is miniatures, a table, a measuring tape, six-sided dice, the scenario that you want to play and, crucially, the ship data cards for the ships you are using. Smoke, splash, fire, flood, flash and searchlight markers are useful too, though there is a page of them in the rules that you can print out.What works well

Scale

Grand Fleets is scaled in 1,000s of yards. That means you can use whatever scale of miniatures you have and whatever sea scale works for the playing area you have available.

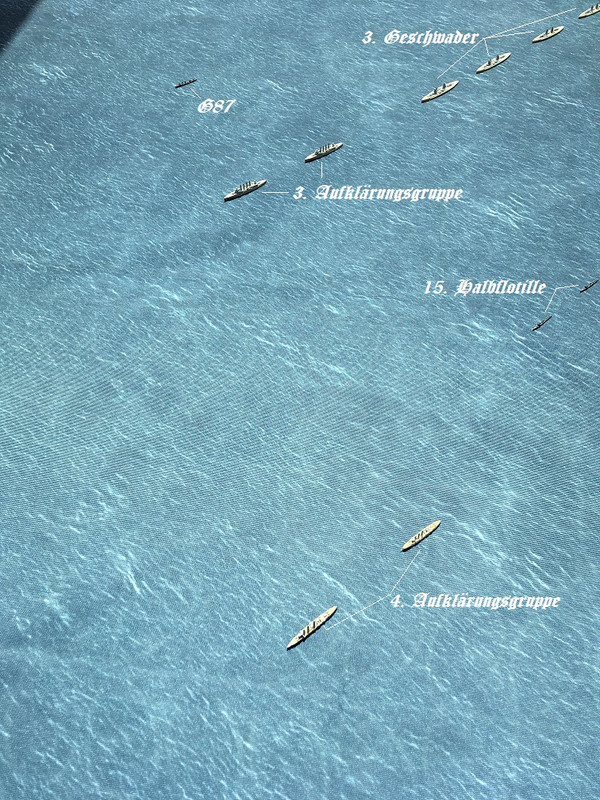

The large guns mounted on capital ships almost always force a compromise between miniature scale and sea scale in age of steam naval wargames. I use 1/3000 miniatures and 2 inches for 1,000 yards (which is 1/18,000), but the rules would work just as well with 10cm or 5 inches as 1,000 yards with a bigger table. Just bear in mind that your miniature ships are probably several times larger relative to distances than the ships they are representing on the table top.Scope

Grand Fleets works well for battles involving anything between two and a dozen ships on each side. I like being able to use the same rules for a clash between a few destroyers or larger squadrons. Destroyers are individual ships, not grouped into flotillas as they are in some rules.The turn sequence

The game has a straightforward turn sequence of initiative, movement, command and combat.Divisions, or squadrons

In Grand Fleets, ships move in divisions, or squadrons.

Ships are divided into divisions (or squadrons) of three to six similar ships, led by a flagship or other divisional leader. This reflects the historical organization of most navies. It is also quicker and easier to move a division of four ships together than to move each separately.

The ships in a division must stay together, within 1,000 yards of each other. Ships that are beyond 1,000 yards from the rest of their division are ‘out of command’, which makes them slower to receive information and react to the enemy, moving first and firing last.Initiative

The initiative is one of my favourite parts of Grand Fleets and plays a crucial role in the game. The squadron or division with the initiative moves last and fires first, giving a substantial tactical advantage. Think of it as certain commanders being more astute, having better situational awareness, having better information from their subordinates or simply having a clearer view through the smoke and shell splashes. The initiative is determined primarily by a roll of the dice, though you can give particular squadron commanders like David Beatty, Franz Hipper, Willis Lee, Gunichi Mikawa, Raizo Tanaka or Philip Vian an advantage if you wish.

The initiative rule adds an element of chance to both movement and combat, avoiding a predictable I Go, You Go sequence. Because firing is not simultaneous and damage takes effect immediately, in theory a squadron with the initiative could destroy an opposing squadron before that squadron was able to fire back.

The obvious flaw in the initiative rule is that if you have multiple divisions in line ahead, as you might at Tsushima, Jutland or Cape Esperance, you can’t very well have your rear division move before your van and centre divisions. The equally obvious solution is for multiple divisions in line to use the initiative roll for the most senior officer, usually the fleet flagship, which is of course what happened historically.

The initiative rule works well for actions in daylight in clear weather, but it doesn’t work so well in poor weather or at night where, historically, ships that spot the enemy first should have the initiative.Movement

Movement in Grand Fleets is straightfoward. Ships can only move directly forward, or turn, with limits on acceleration. The initiative rule means that there’s no need to write orders down. Turning is not tightly proscribed, and there are no turning gauges, which may seem surprising at first, but makes sense for three reasons:

Firstly, unlike the age of sail, or a submarine attack on a convoy, major warships in this era were rarely in close proximity to the enemy. So the exact position of a ship at the end of its move rarely matters.

Secondly, the turning circles of ships are a complex outcome of hull shape, size of ship, size of rudder, speed, sea conditions and even depth of water that defy reduction to a simple rule of thumb, other than that long, narrow, deep vessels with small rudders will turn slower than short, fat, shallow ones with big rudders. According to Norman Friedman: the Iowa-class battleships, fitted with twin rudders, had a tactical diameter of 814 yards at 30 knots; the Fletcher-class destroyers, fitted with a single rudder, had a tactical diameter of 950 yards at 30 knots; the later Allen M. Sumner class, fitted with twin rudders, had a significantly smaller tactical diameter of 700 yards at 30 knots.

Finally, most warships could turn 180 degrees within about 1,000 yards, so proscribing large turning circles makes little sense. For example, the battleship HMS Dreadnought had a tactical diameter of 466 yards at 21 knots and 443 yards at 12 knots, though she turned faster at higher speed. Similarly, the battleship USS New Mexico had a tactical diameter of 690 yards at 21 knots and 645 yards at 10 knots.The gunnery mechanics

For gunnery, each ship rolls a number of dice determined by the arc of its guns, and the range, size, speed and armour of the target.Hitting a fast-moving target with a large gun from a moving platform at long distance is difficult.

The basic gunnery mechanics are quick and simple and work well without extensive measuring or complex calculations. Every ship’s main guns are elegantly abstracted into a single gunnery factor based on the number, size and rate of fire of the guns and the weight of the shells. This number can then be reduced by a number of modifiers for the arc of the ship’s guns, and the range, size, speed and armour of the target. The resulting number is the number of dice that an attacking player rolls to fire at an enemy ship. Every five or six rolled on a D6 results in a hit.

Ships are hit and damaged surprisingly quickly, so if you wanted a slower (and probably more historical) game, you could count only sixes as hits.Historical narrative

The rules work well for recreating naval warfare in the age of steam because the historical balance is right. An armoured cruiser that comes into medium range of a squadron of battleships, as the Defence did at Jutland, is likely to be obliterated. A destroyer flotilla poses a serious threat to a single cruiser, but a single destroyer is unlikely to last long against a cruiser squadron. A destroyer flotilla that presses home an attack on a squadron of battleships or cruisers is likely to suffer losses, but some of the destroyers may be able to get through to launch torpedoes. Historical tactics, like keeping your ships in line and crossing the enemy’s T, work. It’s easy to reconcile the gameplay on the table with history and build a narrative.

There are no national characteristics or superpowers. Japanese torpedoes are remarkably good because Japan’s oxygen-powered Type 93 torpedoes were far faster and longer-ranged than any other navy’s torpedoes. If anything, the rules understate the torpedo’s astonishing performance which repeatedly caught Allied vessels by surprise in 1942.What could be better

Ship data cards

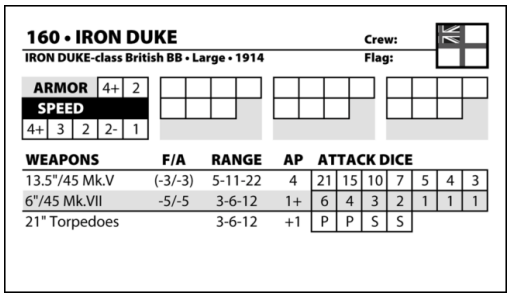

The data card for the battleship Iron Duke.Data cards are common in many modern wargame rules because they save a lot of time looking up gunnery ranges and tracking damage.

However, one of the biggest weaknesses of Grand Fleets Third Edition is that the game doesn’t contain all the ship data cards that most players will want. Although the 160 game cards included in the core game rulebook sounds impressive, many of those are for sister ships (such as 15 British I-class destroyers and 13 British L-class destroyers), so the 50 different ship classes is the more relevant number. Those 50 ship classes are from the six scenarios included in the rules, representing six battles between nine navies across four different wars. So for almost any other historical battle, the core game won’t include the ships that you want. This isn’t a complaint — the rulebook PDF costs $9.99 — just a warning.

There’s good news and bad news here. There are two scenario books with another 160 ship cards each: Tsar & Emperor (http://www.mj12games.com/grandfleets/mjg0732.html) covers the Russo-Japanese War, while King & Kaiser (http://www.mj12games.com/grandfleets/mjg0731.html) covers the First World War. Unfortunately, there is no book of ship data cards for the Second World War, covering the Atlantic, Mediterranean or Pacific theatres. There are only step-by-step instructions on how to create new data cards for any ship.

Fortunately, there’s an invaluable Excel spreadsheet (here: http://www.manbattlestations.com/hostedfiles/GF3StatsGeneratorVer1.1.xlsx) to help you do it, though creating your own data cards for every ship model you have is time consuming and a bit tedious. Without the spreadsheet to create your own ship data cards, the game would be more or less unplayable for the Second World War, beyond the River Plate and Komandorski Islands scenarios.Visibility and sighting

Spotting the enemy first is crucial in a night action.Visibility is included in the advanced rules for Grand Fleets, and at first the rules seem well thought through. The range at which ships can be sighted depends on:

1. The light conditions (whether it’s day or night and the state of the moon);

2. The weather conditions (such as fog, rain and snow);

3. The size of the target (smaller ships are harder to see); and

4. The size of the spotting ship (lookouts are higher up in bigger ships).

However, there are two minor problems with these rules that may or may not bother you. Firstly, the visibility distance is fixed by those parameters, so there is no element of chance and no reflection of the skill of an experienced, trained and alert lookout compared with an untrained, distracted or exhausted one. As written, American, British, German, Italian or Japanese ships of the same size spot each other at the same moment, which doesn’t reflect the Imperial Japanese Navy’s superior night-fighting training in the 1930s or what happened at Jutland in 1916, Matapan in 1941 or in the Solomons in 1942.

Secondly, given the close ranges and high speeds of night actions, moving then sighting, as laid down in the rules, doesn’t work. Ships need to react to sighting the enemy as the range closes during their movement, rather than simply continuing on their existing course. However, there is no mechanism for ships or squadrons to react to sighting the enemy, by altering course, opening fire or both, during their move.Damage resolution

In Grand Fleets, gunnery and torpedo damage cause gradual degradation to the fighting ability of ships. It’s rare, though not impossible (with the critical hit advanced rule), for ships to sink or blow up suddenly in Grand Fleets unless they are hit by torpedoes. So far, so good. Rather than calculating the effects of gunfire damage every time a ship is hit, you work out the effects of damage only when a ship has suffered one third and two thirds damage, which speeds the game up.

But that time saving is lost when you then have to roll a die to allocate damage to the engines, primary and secondary armament and then each torpedo (not even torpedo tube mounting) carried by the damaged ship. That just takes too long in a bigger game. Grand Fleets doesn’t differentiate between damage to the hull of a ship and damage to its upperworks, so the allocation of damage to engines, primary and secondary armament and torpedoes can produce some slightly odd results.

The die rolling gets worse when you add the advanced rule for critical hits. It would be far more efficient to combine damage resolution and critical hits into a 2D6 roll on a single table.What’s broken and needs fixing

Torpedoes

The basic mechanics of firing torpedoes and calculating whether they hit or not mostly work fine. Ships at close range are easier to hit than ships that are far away. Large ships are easier to hit than small ones. Slow, or stopped, ships are easier to hit than fast-moving ones. You work out a few modifiers, roll two dice (2D6) and check the torpedo hit table. If you hit, you then roll a single D6 to work out the damage caused.

However, there are two major problems with the torpedo rules that, unless fixed, can spoil the game as a historical tactical wargame.

Kawakaze ought to be hard for Blue to hit with a torpedo because she is bows on to the Blue. But the rules ignore the facing of a ‘very small’ target ship.The first major problem is that the rules barely account for the facing of the target ship. Having a ship’s bow or stern, rather than broadside, facing to torpedoes makes no difference in most situations. Oddly, the facing of the target ship only matters if the ship is ‘large’ (most super-Dreadnought battleships) or ‘small’ (most cruisers), but not if it’s ‘very small’ (all destroyers and small cruisers), ‘medium’ (smaller battleships) or ‘very large’. This is a major flaw in the rules because the standard response to a torpedo attack throughout the age of steam was for ships to turn away from (or, sometimes, to turn towards) the torpedoes to comb the torpedo tracks. A typical Second World War cruiser was nine, 10 or even 11 times longer than it was wide, while even a pre-Dreadnought battleship like Togo’s Mikasa was 5½ times longer than it was wide. So, all other things being equal, a destroyer or cruiser that is broadside on (perpendicular) to the track of the torpedoes is about 10 times more likely to be hit by a torpedo than a destroyer or cruiser that is parallel to the track of the torpedoes. Additionally, a fast ship doing 30 knots is nearly as fast as a 40-knot torpedo, so a fast ship that turns away from a torpedo not only has more time to take avoiding action: it might even outrun the torpedo until the torpedo’s fuel runs out.

The second major problem is that torpedoes are treated like gunfire and resolved in the turn that the torpedo is fired — i.e. without the target ships having any opportunity or necessity to take avoiding action. That simplifies and speeds up the game, because you don’t need to track torpedoes from one turn to the next. But by removing the decision on how to respond to a (real or feint) torpedo attack, resolving torpedo attacks in the same turn undermines Grand Fleets as a tactical wargame. The tactics and outcomes of battles like Jutland in 1916, the Barents Sea in 1942 and the Dogger Bank in 1915 would have been completely different without the need to avoid torpedoes.

One last niggle is that rolling two dice for every torpedo, rather than for a salvo of torpedoes fired at the same target, can become time consuming in large battles with a lot of destroyers, or destroyers that carry a lot of torpedoes. Resolving a full torpedo salvo from three Fubuki-class destroyers requires throwing 27 pairs of dice.Radar

In the advanced rules in Grand Fleets radar plays a role in gunnery, but not in sighting enemy ships. In effect, the rules encompass gunnery radar, but not surface search radar.

The visibility rules take no account of whether a ship was fitted with radar or not. As early as April 1940, the German battleship Gneisenau picked up the presence of the British battlecruiser Renown 10 minutes before she could be seen against the dark western horizon. SG radar, in particular, gave American ships fitted with it, such as the cruiser Helena at Cape Esperance in October 1942, the ability to spot approaching Japanese ships long before they were visible with binoculars. While some American commanders failed to understand or profit from the capability, SG radar eventually gave American ships in the Solomons a substantial advantage over the Japanese at night. So radar ought to play a role in who spots who first.Amendments that work for me

Every wargamer looks for a different balance between a fun game and a historical simulation. To make the rules work better for me, I have amended the rules in two areas: sighting and initiative, and torpedoes.

Instead of rolling two dice (2D6) for the initiative, I use the same 2D6 dice roll both to spot the enemy and to determine which squadrons have the initiative.

– I have introduced a sighting table that introduces an element of chance, training and radar, in addition to light conditions;

– I give the initiative to squadrons that sight the enemy first; and

– I let ships alter course from the point at which the squadron flagship sights the enemy.Summary

Overall this is a strong set of rules. The core rules and mechanisms are simple and work well. The rules as written work well for gaming an engagement between two fleets on a clear sunny day when both sides can see the other coming. They don’t work so well for gaming daylight actions in the misty North Sea from 1914 to 1918 or night actions in the Solomon Islands in 1942 when ships that spotted their opponents first were at a substantial tactical advantage. By making a few changes, I have found a balance between fun game and historic simulation that works for me.

You can buy the rules, and the supplements, on Wargames Vault here: https://www.wargamevault.com/product/146384/Grand-Fleets-Third-Edition. They are usually $9.99, but seem to be on sale for $7.49. A bargain. Recommended.17/10/2022 at 15:17 #179168 Darkest Star GamesParticipant

Darkest Star GamesParticipantGreat review and advice. I’ll steer a buddy to this write up as he is looking at playing WW1 actions and hasn’t decided on a rule set or scale yet (and it’s been like 4 years he’s been pondering…). Many thanks!

"I saw this in a cartoon once, but I'm pretty sure I can do it..."

17/10/2022 at 22:31 #179204 Tony SParticipant

Tony SParticipantI really appreciate the time and effort for this detailed review. Very well done. Thoroughly enjoyed reading your thoughtful observations.

26/10/2022 at 17:50 #179552 AdmiralHawkeParticipant

AdmiralHawkeParticipantGreat review and advice. I’ll steer a buddy to this write up as he is looking at playing WW1 actions and hasn’t decided on a rule set or scale yet (and it’s been like 4 years he’s been pondering…). Many thanks!

I really appreciate the time and effort for this detailed review. Very well done. Thoroughly enjoyed reading your thoughtful observations.

Thank you both. I’m glad you enjoyed it. 🙂

-

AuthorPosts

- You must be logged in to reply to this topic.